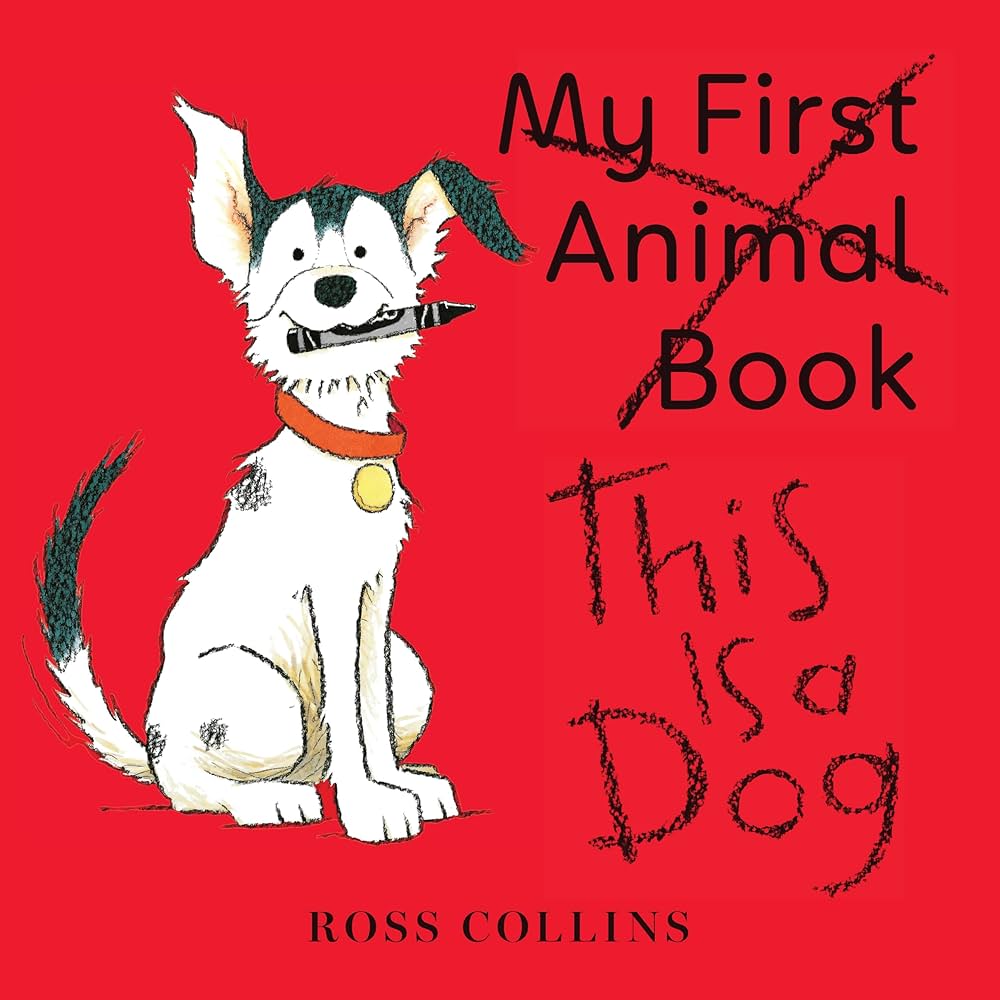

Title: The Significance of “This Is a Dog”: A Multifaceted Analysis

Introduction

In everyday speech, the short sentence “this is a dog” quietly demonstrates how humans carve order out of chaos. It is a miniature lesson in naming, grouping, and sharing ideas. By unpacking this modest statement, we can glimpse how language, thought, and social life intertwine.

Language and Categorization

Words let us sort the world into manageable chunks. Saying “this is a dog” follows a clear pattern—subject, verb, complement—that tells everyone within earshot how to file the animal in view. Beneath the grammar lies a mental habit: we instinctively treat the creature as a familiar example of “dogness,” a fuzzy-edged category held together by shared traits such as shape, sound, and behavior.

This mental shortcut is not just convenient; it is necessary. Without quick labels, every new sight would demand a fresh decision. The phrase acts as a cognitive anchor, letting speaker and listener move on to richer talk about size, mood, or the need for a leash.

Communication and Semantics

Three small pieces—this, is, dog—form a sturdy bridge between minds. “This” points a mental finger; “is” asserts existence; “dog” supplies the class. Each party must already know what dogs typically are, or the message collapses. Thus the sentence is both trivial and fragile: trivial because toddlers master it, fragile because it rests on a hidden mountain of shared knowledge.

When the sharing works, conversation flows. A single utterance can launch stories about breeds, training tips, or warnings about an approaching bark. The humble sentence becomes a doorway to cooperation.

Societal Implications

How we name animals shapes how we treat them. Calling a creature “dog” rather than “stray,” “pet,” or “worker” nudges attitudes and policies in different directions. Labels influence feeding, housing, medical care, and even legal protections. In that sense, a casual identification carries ethical weight.

The word also mirrors human history. Dogs have walked beside people for millennia as guardians, hunters, and companions. Each time we say “this is a dog,” we echo countless earlier voices who used the same term to invite an animal into the circle of daily life.

Empirical Evidence and Research

Developmental studies show that before their second birthday, children confidently sort dogs from cats or foxes, even when the pictures are novel. Such findings hint that the brain arrives prepared to carve nature at its joints, then refines the cuts through experience.

Linguistic research adds that every language offers its own carving tools, yet the urge to name and share remains universal. Together, these strands suggest that simple statements like “this is a dog” are surface ripples of deep cognitive currents.

Conclusion

“This is a dog” is more than a label; it is a social act, a cognitive reflex, and a cultural echo. It reminds us that classification is not sterile bookkeeping but a living process that guides attention, affection, and responsibility.

Recognizing the power of such everyday words encourages clearer communication and more thoughtful choices—from the way we describe shelter animals to how we design urban spaces that accommodate both people and their four-legged neighbors.

Continued study of how we name, share, and revise categories will keep illuminating the quiet mechanics of human understanding, one plain sentence at a time.