Introduction

Many people assume every ginger cat is a boy, but the truth is more nuanced. This article explains how feline coat color is inherited, why tomcats are more often orange, and why exceptions still appear in female litters.

Genetic Background

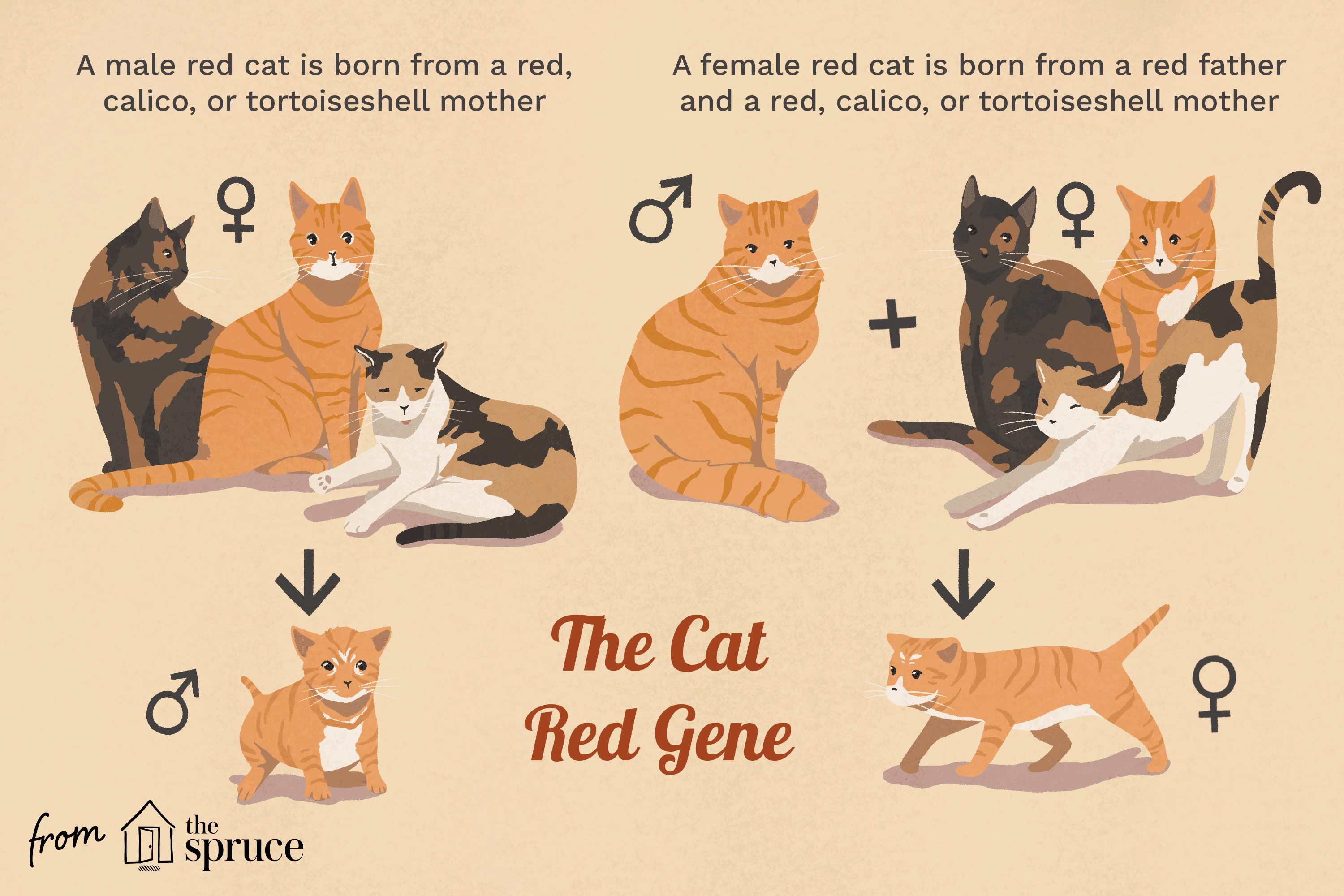

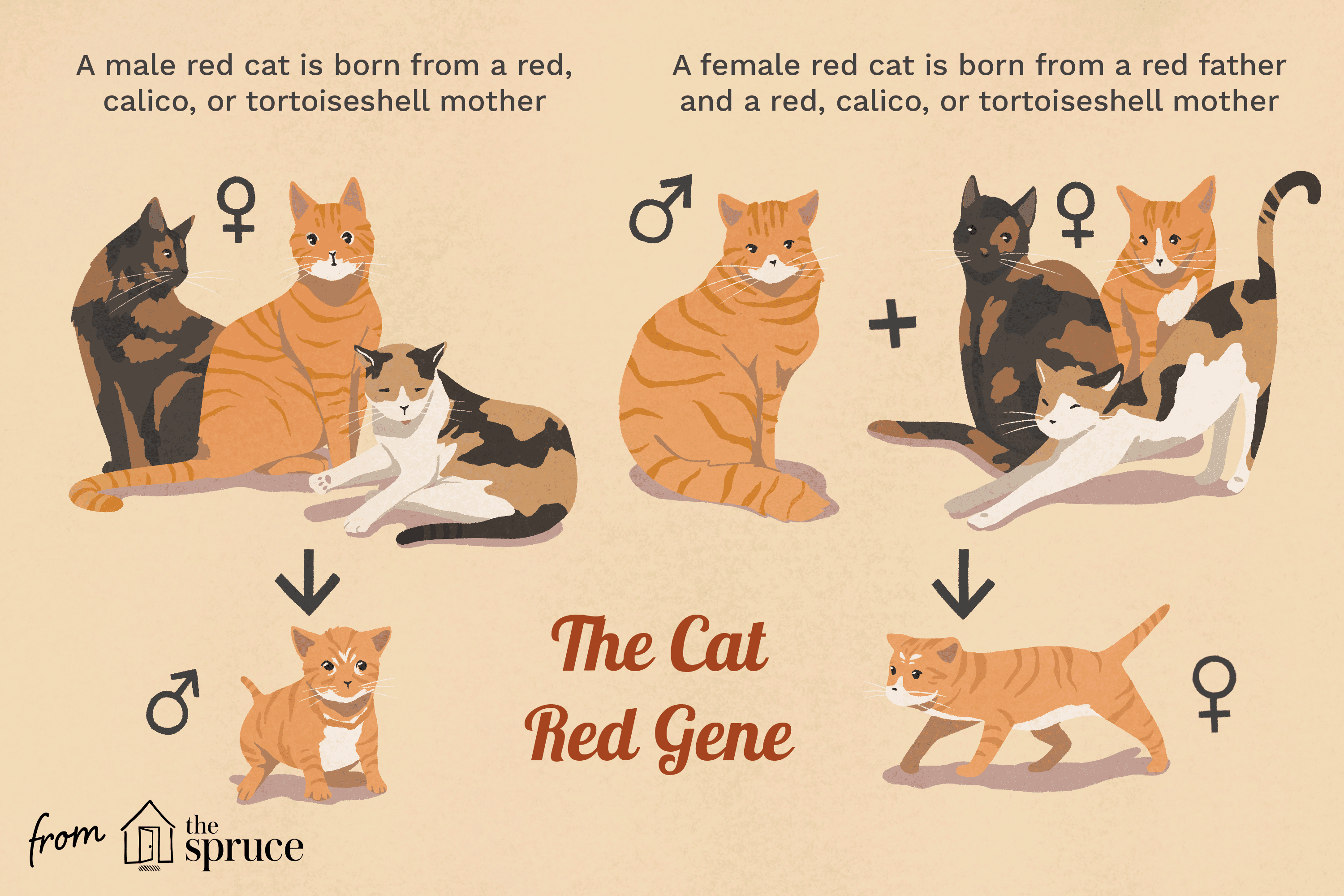

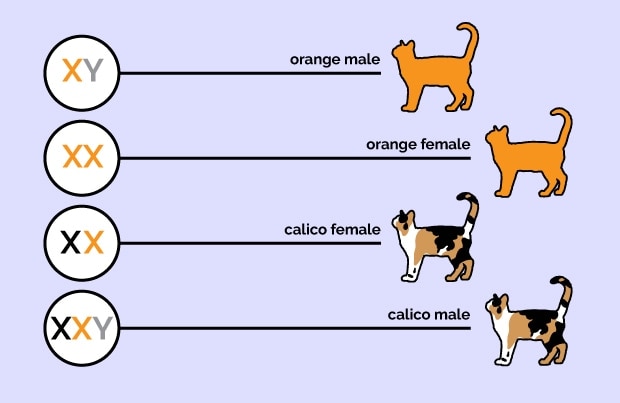

Coat color in cats is controlled by several genes. The most influential is the “O” gene, which allows orange pigment to replace the default black or brown. Because this gene sits on the X chromosome, its expression is tied to the cat’s sex chromosomes.

Males carry one X and one Y, so a single O allele turns them ginger. Females have two X chromosomes; they need the allele on both copies to be fully orange, making the outcome statistically less likely.

The X-Linked Gene Theory

The simple version of the theory says “orange equals male,” yet biology rarely follows absolute rules. A female can display the color if both X chromosomes carry the allele, or if unusual patterns of X-inactivation leave most fur cells expressing the orange version.

Anecdotal Evidence

Owners and shelters regularly post photos of orange queens, proving the color is not exclusive to toms. These everyday sightings remind us that genetics deals in probabilities, not certainties.

Scientific Research

Peer-reviewed work confirms the X-link but also documents modifier genes that lighten, darken, or patch the coat. Breed surveys show that while most solid-orange cats are indeed male, a small, steady percentage of females share the shade.

Conclusion

Ginger coats favor males for genetic reasons, yet females can and do wear the color. The exceptions enrich the feline palette and underscore how diverse heredity can be.

Recommendations and Future Research

Continued study could clarify:

1. How additional pigment genes interact with the O locus.

2. Whether certain breeds carry higher rates of orange females.

3. The exact mechanisms behind rare uniform-orange queens.

Such investigations will deepen our appreciation of the subtle science hidden in every tabby, tortie, or solid-ginger companion.